The popular belief that the seven million Americans who lost their homes to foreclosure during the Housing Crash are healed, whole and forgiven of their debts after seven years have passed is only partly true.

For foreclosures, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac set a seven-year waiting period before defaulters can apply for a mortgage, measured from the completion date of the foreclosure action. With time foreclosures, bankruptcy filings and tax liens disappear from credit records but the impact of their misfortune lingers for years in the form of substandard credit ratings and scores.

A new study from the Urban institute, The Lasting Impact of Foreclosures and Negative Public Records, corrects the conventional wisdom by chronicling the painful punishment suffered by victims of the foreclosure floods and the Great Recession that began in earnest a decade ago and the impact not just upon individual families but on the economy as a whole.

The researchers found that It takes a long time for a consumer’s credit score to recover from the impact of a foreclosure—far longer than the seven years the foreclosure remains on the credit report.

From 2004 through 2015, 7.1 million borrowers experienced a foreclosure filing, and 34.4 million consumers acquired an adverse public record other than foreclosure. Altogether, 41.5 million people, or 16 percent of the 264 million US consumers with credit records, experienced a financial crisis that impacted their credit.

“We believe this extended impact at least partially explains the slow recovery after 2010, the study found,” wrote the authors, Wei Li, Laurie Goodman and Denise Bonsu.

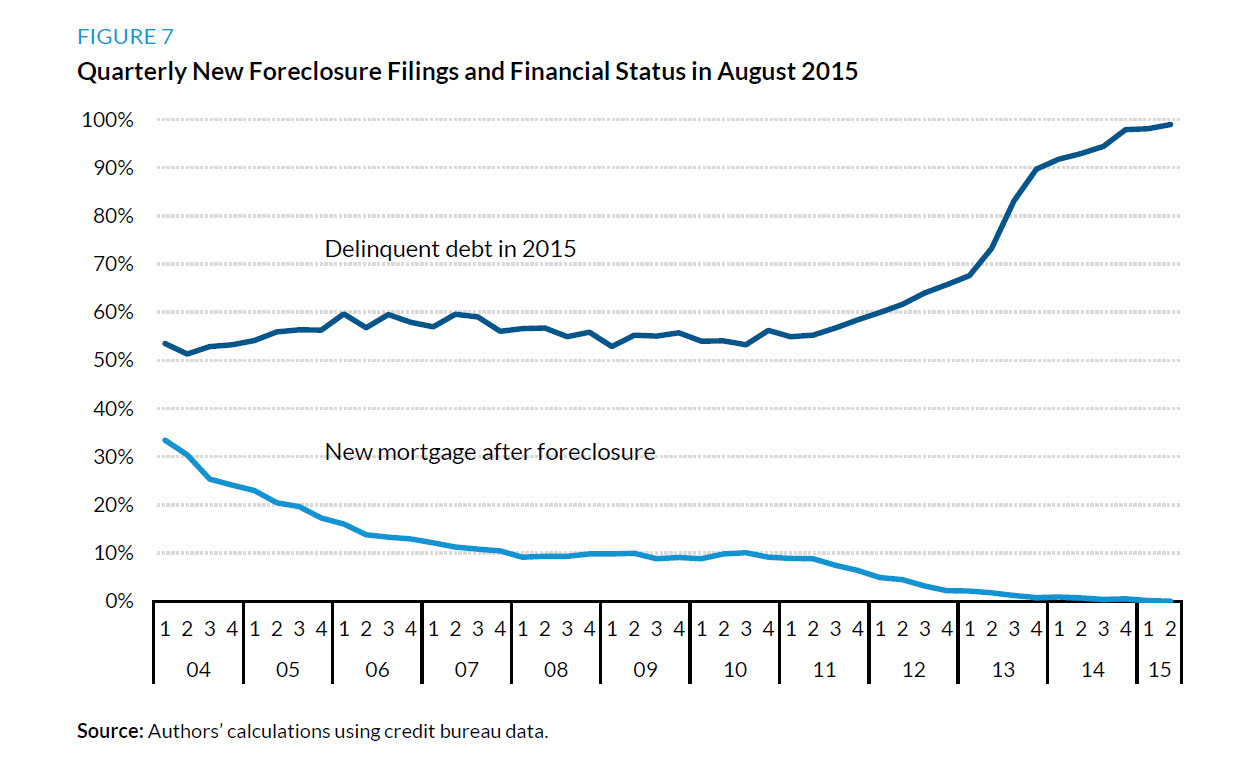

More than 60 percent of consumers with these negative financial events still had VantageScore credit scores below 620 in 2015. More than 60 percent of them had delinquent debt in 2015, and only 8 percent of them were able to obtain new mortgages as of 2015. And, more than 70 percent of them were the age that preferred homeowning (between 29 and 59 years old) in 2015; this large group of potential borrowers with negative financial events profoundly affects the homeownership rate.

At least at the peak of crisis, when the spike in foreclosure filings jammed up judicial foreclosures, the long judicial foreclosure process might have prevented foreclosed-upon borrowers from moving on.

A large number of consumers will retain adverse events on their records for a considerable time, making it hard for many of them to borrow again. At the end of 2018, 22.8 million consumers—almost 9 percent of the adult consumer population—will still have a foreclosure or adverse public record.

Middle-aged consumers were hit hardest by these credit blemishes. Seventy-three percent of consumers (30 million) who experienced foreclosure or other adverse public records were between 29 and 59 years old in 2015, yet this age group accounts for only 53 percent of adult consumers. The middle-aged consumers hit hardest by these adverse credit events have had a profound impact on the homeownership rate because their age group has the strongest preference for homeownership.

The authors suggested that the United States has experienced such a sluggish recovery from the Great Recession at least in part because of the magnitude of the damage to consumer credit records during the 2008–09 financial crisis and the very slow recovery of many of those consumers. The lingering effects of foreclosures and adverse public records prevent consumers from obtaining mortgages and pursuing homeownership, hinder the recovery of the housing market, limit consumers’ ability to obtain other credit such as auto loans, and reduce their ability and willingness to spend (Hurd and Rohwedder 2010). These adverse impacts in turn weaken the strength of the economic recovery in a vicious cycle.