More people live in Riverside – population 330,000 – than are registered voters of the Libertarian and Green parties in all of California.

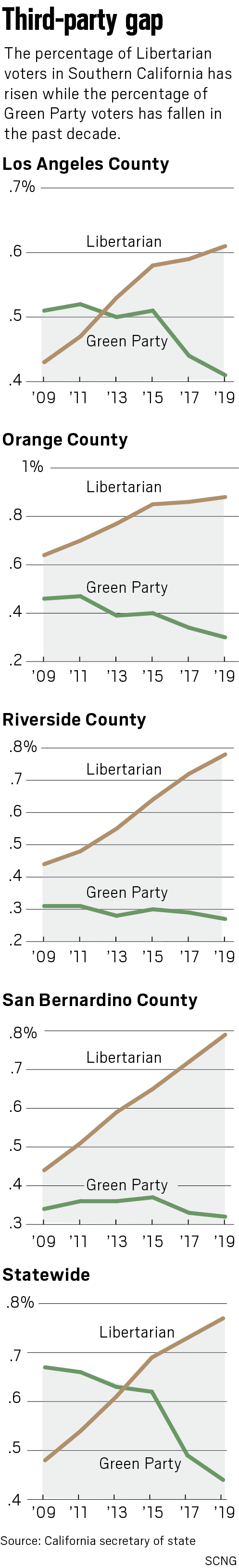

But numbers-wise, the parties, which together account for 1.2 percent of all California voters, are heading in opposite directions. Between February 2009 and February 2019, the socially liberal, economically conservative Libertarian Party of California added 70,000 voters.

Meanwhile, during the same decade, the left-of-center Green Party of California lost more than 27,000 voters, potentially putting it closer to losing its status as a qualified political party than can appear on the ballot, California voter registration figures show.

Neither party figures to have major influence over California politics anytime soon. But California Libertarians are heartened by gains in the voter rolls and at the polls, especially Libertarian candidate Jeff Hewitt’s upset victory last November in the race for a supervisor seat in Riverside County.

“Here in California, we’re beginning to resonate because people are learning more about us,” said Honor “Mimi” Robson, the state Libertarian Party chair who advanced out of last year’s primary for a Los Angeles County Assembly seat before losing to a Democrat in the November general election.

Democrats remain the dominant party in California, accounting for 43 percent of all registered voters as of February. The party holds all statewide offices, a supermajority in the state Legislature and 46 of the state’s 53 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Democrat Hillary Clinton carried California in 2016, with 62 percent of the vote to Donald Trump’s 32 percent. Libertarian nominee Gary Johnson was third, with roughly 3 percent of the vote, while Green Party candidate Jill Stein placed fourth with 2 percent.

After Democrat, the second most popular voter registration label in California is “no party preference,” which accounts for 28 percent of all voters. Republican is No. 3, accounting for 24 percent of all registered voters – a steep decline over the past year and reflective of a long-term slide for the GOP in California.

But in the world of non-brand names, politically speaking, Libertarian and Greens aren’t alone. Technically, data shows that the state’s biggest third party is the American Independent Party, at about 3 percent of all registered voters.

But many argue that the American Independent registration numbers are misleading, noting that the party’s use of the word “Independent” confuses voters who believe they’re signing on for a neutral group when, in fact, the party leans far right.

Taking the American Independent Party out of the equation, the two biggest third-party labels in the state are Libertarian and Green. As of this year, Libertarians make up 0.77 percent of the state’s registered voters, while Greens account for 0.44 percent. A decade ago, those numbers were nearly reversed.

In California, the threshold to qualify as a party through voter registration – meaning candidates are listed on state and local ballots – is 0.33 percent.

“An alternative”

The fact that Libertarian registration has “steadily increased” since 2009, is probably “more ideologically than candidate-driven,” said Marcia Godwin, a professor of public policy at University of La Verne.

Libertarians offer a blend of liberal and conservative ideas. They tend to support gun rights, cutting regulations and free-market capitalism, but they also endorse abortion rights, LGBTQ rights and ending the war on drugs.

While Libertarians didn’t see a registration spike following President Donald Trump’s election, Godwin noted that the party might be viewed as an alternative for voters “who support limited government and privacy rights without wanting to subscribe to social conservatism.”

Libertarian leader Robson said that, in her view, even as Democrats have gotten “out of control” with their one-party rule in California, the GOP’s conservative cultural outlook and loyalty to Trump aren’t resonating with state voters.

That dynamic, Robson believes, opens the door for Libertarians in California. Another key, she said, is the election of Hewitt, a Libertarian National Committee member and former mayor of Calimesa who came from behind to defeat a better-funded, well-known opponent – former GOP assemblyman Russ Bogh.

“In the past, the Libertarian Party hasn’t done a really good job of running good candidates for obtainable offices,” Robson said, Now, she added, the party is focusing on candidates like Hewitt who can win local races before running for bigger offices.

Boris Heersink, an assistant political science professor at Fordham University in New York City, attributes Libertarians’ recent growth to the 2011 start of California’s top-two primary system, which sends the top two vote-getters in a June primary, regardless of party, to the November general election.

That system, Heersink said, gives third-party candidates a slightly higher chance of success. Last year, he said, six Libertarian candidates finished in the top two in primaries and wound up on the November ballot for state legislative seats. They didn’t win — this time — but their prospects were improved by being in head-to-head match-ups.

“That is still arguably a better performance than you’d get in other places without such a system,” Heersink said.

But Laura Wells, who ran for a Northern California congressional seat in 2018 as a Green, said the top-two system has had a “terrible effect” on third-party candidates. She said it “narrows choices” in general elections, creating advantages for well-financed, well-known Democratic and Republicans candidates.

Bernie a draw?

Though the Green Party reached a recent peak in 2003, with nearly 1 percent of all voter registrations in California, it’s been fading since.

“The presidential candidates have not been as high-profile since (Ralph) Nader’s campaigns. And it can be argued that his role as spoiler in the 2000 (presidential election) even turned voters away from registering as Greens,” Godwin said.

“(And) the California Democratic Party also seems to have co-opted a lot of the Green Party positions.”

Green candidate Wells believes Bernie Sanders – a self-described democratic socialist, who, like the Greens, advocates for social justice and against income inequality while supporting a broad range of social programs – has something to do with the party’s registration decline in California.

“When you look at (the Green Party’s values) and what Bernie had been saying in 2016 and now leading up to 2020, a lot of the values that he expresses are very similar to the Green Party,” Wells said.

“From a progressive point of view, he’s the best candidate that’s run with the major parties in most people’s lifetime.”

Many Greens, Wells said, registered as Democrats in 2016 to boost Sanders’ bid for the Democratic presidential nomination. “Some people came back to re-register as Green and some didn’t,” she said.

To secure a ballot spot, political parties in California must have voter registration numbers equal to 0.33 percent of all registered voters by Oct. 1, 2019 or July 3, 2020. Parties also can qualify by getting roughly 1.271 million voter signatures on petitions by Oct. 20, 2019 or June 21, 2020.

Despite the loss of registered voters, Wells is confident the Green Party won’t lose its qualified-party status.

“We’re strong enough to do what it takes,” she said.